New on Shfl, September 2025

Chris Catchpole on él Records, Joe Muggs on Compass Point, Sean Wood on Mahler, Rick Anderson on 80s Hardcore, plus fifteen new recommendations

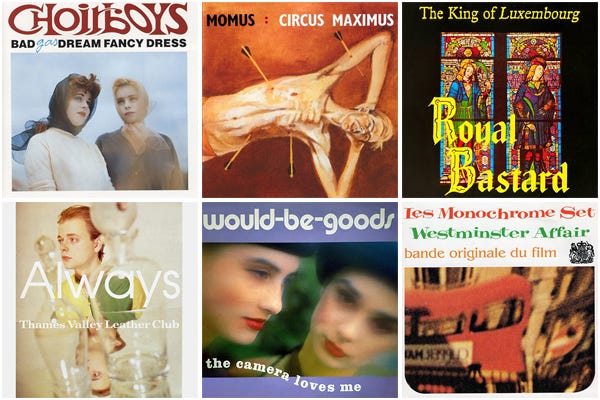

Chris Catchpole on él Records

At odds with how labels were run at the time, independent or otherwise, Alway saw himself more like a 1960s impresario and svengali than someone who signed artists they liked and thought might sell a few records — not so much taking a hands-on approach as wielding complete control over every aspect of the label’s output, from the artwork right down to choosing the song titles.

Collections

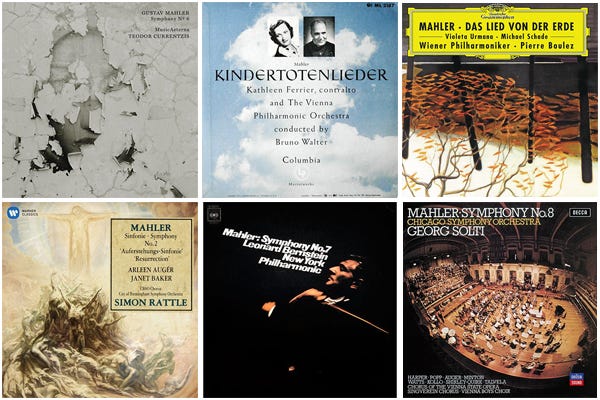

Sean Wood on Mahler

Despite the amount of ink spilled by Mahler and others about the meanings of his music, it is important to not forget that he was ultimately a working musician, a great orchestrator, someone capable of composing striking and ambiguous musical ideas that invite interpretation without providing easy answers.

Joe Muggs on Compass Point

There are a select group of producers who helped define the high-gloss, aspirational sound of the 1980s. Nile Rodgers, Trevor Horn, Quincy Jones, Brian Eno with Daniel Lanois, “Jellybean” Benitez stand out, for example. But very few did the job with quite as much class and style as Island Records founder Chris Blackwell and studio wizard Alex Sadkin.

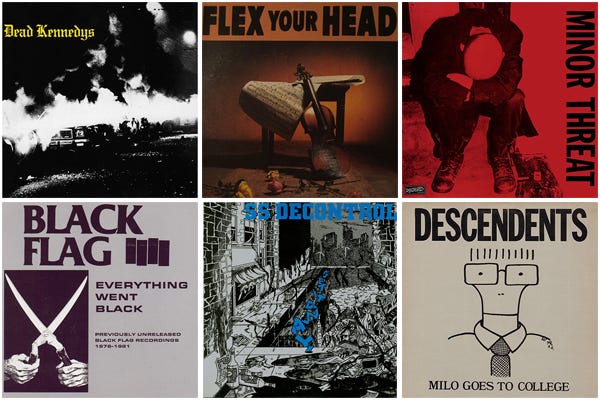

Rick Anderson on 80s Hardcore Punk

But punk was more than just a reaction; it also exploded existing boundaries of musical decorum, and by doing so it opened the floodgates to a wide variety of new genres that owed a debt to punk but were not at all the same thing.

Reviews

Harold Heath

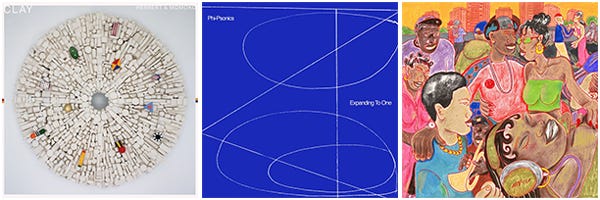

Kokoroko — Tuff Times Never Last

The seçond album from London 8-piece 21st century Afrobeat jazz powerhouse Kokoroko, on Giles Peterson’s Brownswood label, serves up an expertly played set of joyous, sweet-soul and R’n’B flavoured Afrobeat and highlife hybrid jazz tracks.

Phi-Psonics — Expanding to One

The style is spiritual, devotional jazz from the serene-and-controlled rather than fiery-and-furious school, the intensity rising from their unhurried, dedicated slow-burn approach and the magic that can occur when musicians lock in and ride the peaks and troughs together.

Momoko Gill & Matthew Herbert — Clay

Songs are built from bubble sounds, softly undefined synth chords, plucks and chimes with questionable provenance, hard-to-place angular percussion, with Gill’s drums carefully entering the sound field and providing either subtle drive or rhythmic fire when required.

Hank Shteamer

Unwound — The Future of What

Unwound’s evolution from scrappy, cathartic post-hardcore outfit to visionary art-rock ensemble was a gradual one, and their third LP, The Future of What, finds them at a marvelously assured midpoint on that creative journey.

Beherit — Drawing Down the Moon

Some early-’90s black metal is prized for its rawness and ferocity, but this LP — the debut full-length from Finland’s Beherit — earned canonical status largely due to its unsettling weirdness. The genre’s familiar blast and bludgeon is here, but it’s seasoned with constant surprise.

Dazzling Killmen — Dig Out the Switch

Through marathon practices and an eclectic array of influences ranging from the Minutemen to Captain Beefheart, the trio of guitarist-vocalist Nick Sakes, bassist Darin Gray and bassist Blake Fleming honed a bizarre yet entirely coherent sound that landed somewhere between explosive post-hardcore and labyrinthine prog.

Andy Beta

Okkyung Lee — just like any other day (어느날) : background music for your mundane activities

Her oeuvre – over 30 releases – often documents prickly, challenging exchanges with the likes of Bill Orcutt, Christina Marclay, or Evan Parker, but Just Like Any Other Day isn’t just like her previous efforts. For one, Lee relies heavily on twinkling synthesizers, her exquisite bow work on cello (her primary instrument) nowhere to be heard.

Amina Claudine Myers — Solace of the Mind

Maybe the jazz press just resented her forays in the 1980s to embrace R&B, funk, and soul, but pianist Amina Claudine Myers always sought a common ground between her church upbringing in the American South, the Chicago and New York jazz scene, and popular music formats blaring on the radio.

Mal Waldron — Candy Girl

Candy Girl was always an enigma in Waldron’s catalog, a blip in 1975 and long since out of print. At times, it was mistaken for Parisian funk band Lafayette Afro Rock Band, as members of that band served as his backing band. It’s a rare glimpse of Waldron on Fender Rhodes, with Frank Abel on clavinet.

Chris Catchpole

Serge Gainsbourg — Casino De Paris 1985

The 80s didn’t look kindly on many 60s icons, yet this rare 1985 live outing six years before his death found Serge Gainsbourg in defiant form. As might be expected, the legendary bon viveur is audibly drunk for most of it, and while the slickness of his contemporary backing band might seem like an odd fit — fretless bass, yacht-rock guitar, squealing saxophone — it’s magnificent, like putting a Rottweiler in an Armani suit, as Serge growls, weaves and presumably chain-smokes his way through glossy renditions of his work with a bite and menace that frequently outstrips their studio counterparts.

Saint Leonard — The Golden Hour

Kieran Leonard’s third album was written and recorded while the singer was hunkered down in East Berlin through a bitterly cold winter during the height of lockdown, Nathan Saoudi and Alex White from notoriously debauched South London degenerates The Fat White Family serving as both his musical collaborators and guides through the city’s illicit underbelly.

Various Artists — Songs For A Central Park Picnic

Stanley and bandmate Pete Wiggs’ Songs For… series of compilations present impeccably curated playlists for a variety of settings, from rainy afternoons to 1950s teahouses, and fuggy, pre-smoking ban pubs. Songs For A Central Park Picnic lays out a suitably tasteful spread of New York-centred, pre-Beatles pop.

Joshua Levine

Oasis — (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?

Oasis’s classic 1994 debut, Definitely Maybe, had synthesized different strains of rock and roll made by British outcasts, from the mods to the Pistols to The Smiths, delivered in a defiant sneer for the ages. The result, in the UK, was a huge pop hit, and Oasis were no longer in the underclass. With a new, more technically proficient drummer, a year later, they followed it up with (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, one of the best-selling albums in British history. The point of Oasis was finding shared humanity in raw, sometimes unflattering honesty, and that’s the thread that connects both records.

Oasis — Be Here Now

The conventional wisdom is that Oasis lost the plot on this, the Britpoppers’ third album, in a blizzard of cocaine and fame-induced hubris. That view informed Be Here Now’s reputation for years – that it was one of rock music’s all-time disasters and flops. Far removed from its moment, it doesn’t quite reach the level of the two classics that preceded it (not much does), but Be Here Now has flashes of brilliance that are propped up by its excess, epic song lengths and endless instrumental overdubs.

George Harrison — All Things Must Pass

All Things Must Pass was a self-consciously massive and myth-making statement. Designed to showcase George Harrison’s songwriting (by this point equal to his former bandmates Lennon and McCartney), it was the first three-record set of studio recordings, and compiled songs that had been ignored by The Beatles, sometimes for years.