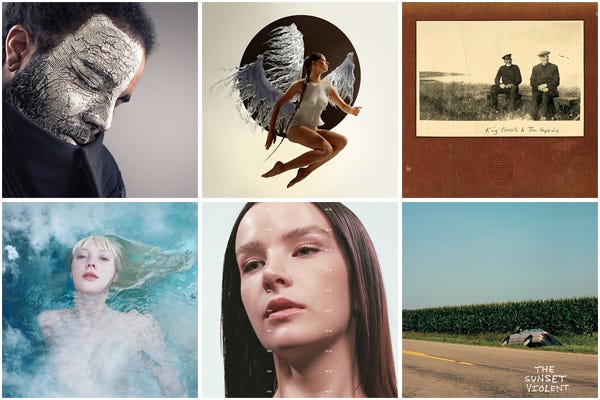

New on Shfl, January 2025 (Best of 2024 Edition)

Joe Muggs on Indietronica, Sean Wood on Renaissance Polyphony, Harold Heath on Leng Records, Joshua Levine on Bollywood Disco and 12 new recommendations plus our Best of 2024 list

Miscellany

Shfl’s Best of 2024. Dig in :)

Joe Muggs on Indietronica

The nature of musical genre took a dramatic flip around the turn of the millennium. In fact you can probably pin it down to June 1999 when Napster was launched, ushering in the everything-everywhere-all-at-once era of mass availability of all styles and eras of music to the curious listener. In the post-rock’n’roll second half of the 20th century, styles tended to be linked to revolutionary moments in time, geographical scenes technological or pharmaceutical shifts, and recognisable style tribes, and thus relatively easy to define – but now, suddenly definitions were loosened, development less linear, everything generally became mixed and muddled.

Collections

Sean Wood on Renaissance Polyphony

There is in fact, a whole universe of different affects in the music of this period; irreverent humor (Lassus’ “Quant mon mary vient de dehors”), poetic eros (Arcadelt, “Il bianco e dolce cigno”), onomatopoetic play (Janequin’s “La Bataille”), and religious feelings ranging from the totally sober (Palestrina) to the totally lavish (Gabrieli). And there is a range and diversity of contemporary performing styles, too, ranging from the studious (The King’s Singers) to the outrageous (Ensemble Clément Janequin).

Harold Heath on Leng Records

Generally churning away at the mid-tempo-to-chug end of the house/disco spectrum, the Leng sound is the coalescence of a broad shared set of influences, the weaving together of strands from several musical traditions into something that sounds both familiar and new.

Joshua Levine on Bollywood Disco

The music in early masala films tended to be in a slow and sentimental ballad style, but the immense global success of 1977’s Saturday Night Fever helped change that. Its influence was felt worldwide, including in Mumbai, where directors and producers saw the potential for adapting disco music and melodrama to Hindi and hopefully replicating its box office receipts.

Reviews

Phil Freeman

Attic — Return of the Witchfinder

Cagliostro’s voice continues to be a genuinely uncanny King Diamond impression most of the time, but at a few points he delivers dramatic recitations that bring to mind Iron Maiden’s Bruce Dickinson. This is the album on which Attic have graduated from just doing the thing they love to having a style of their own, and they’ve written some genuinely headbang-worthy songs in the process.

Bedsore — Dreaming the Strife for Love

What the Italian band Bedsore (I know, gross) asks us to consider is, What if death metal had actually started fifteen years before that, in Europe? Their astonishing second album blends crushing metal riffs with vintage organ and synth sounds, ethereally operatic and wordless female vocals, and ever-shifting time signatures to create something that crosses vintage Opeth with the dark art-rock of Van der Graaf Generator and Univers Zero, blends Goblin’s soundtracks to Dario Argento films with the short-attention-span thrash blasts of Mike Patton’s Fantômas, and calls back to an earlier landmark of jazzy, proggy extreme metal from Italy: Ephel Duath’s head-spinning 2003 masterpiece The Painter’s Palette.

Roland Kayn — Simultan

Simultan, a triple LP recorded between 1970 and 1972 and released in 1977, was Kayn’s debut, and his masterpiece. Listening to it, it’s possible to hear previews of everything from Autechre to Merzbow, and while its compositional logic is both inhuman and somewhat implacable, it has an eerie beauty. It’s a symphony of hum, crackle, crunch, and pulse, totally lacking in conventional rhythm and yet throbbing with life.

Nate Patrin

Ka — The Thief Next to Jesus

Where does your morality come from when you’re disillusioned by the church? For one of the most incisive albums of his career — and the last released in his tragically cut-short lifetime — Kaseem Ryan examines that question with the perceptive clarity and quiet power that made him one of the great sociologists of early 21st Century hip-hop.

Greg Foat — The Glass Frog

As glossy and poised as the material on The Glass Frog often sounds, its resemblance to a strain of jazz that brings up associations with library music or adult-contemporary or “fuzak” — or any other commercial-friendly trends purists found disreputable in the latter decades of the 20th Century — actually works to its advantage. Because for all its air of frictionless, high-fidelity polish, there’s an affecting emotional tinge to these performances that unsettles simple placidity.

Xylitol — Anemones

DJ/producer Catherine Backhouse, a/k/a Xylitol, is a disciple of what Simon Reynolds calls the “hardcore continuum,” the evolution of dance music that mutated acid-house-fueled rave into jungle and its frenetic sonic offshoots. Her Planet Mu debut Anemones encompasses that world with the kinds of familiar, instantly-recognizable break samples and drum patterns any Metalheadz or Moving Shadow devotee would perk their ears up for. But the throwback signifiers aren’t the whole package; her sound sprawls in both directions chronologically and takes unpredictable retrofuturist routes through every possible d’n’b-compatible strain of dance music she can fit into it.

Amelia Riggs

Landlady — Upright Behavior

By the thunderous ending of opening track “Above My Ground,” Landlady has already done more to set themselves apart from the aloofer popular indie groups in five minutes than most could in five albums.

Nick Cave — Ghosteen

Like Nick Cave’s previous monuments to living in the shadow of pain, GHOSTEEN is not the cut and dry “here’s how I’ve been coping since losing my children” album that lets the audience off easy with gloom and minor bursts of catharsis.

Titus Andronicus — The Monitor

The Monitor is Jersey punks Titus Andronicus’ second album, but every note is wrung out and hollered like it could be their last. Framing a breakup through the lens of getting really, really into the history of The American Civil War is a preposterous endeavor, but frontman Patrick Stickles weaves tales of melancholic self-loathing and paranoia with the same precision as the editors of a Ken Burns documentary.

Sean Wood

Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band — Hammersmith Odeon, London ‘75

A titanic feat of live performance that stands tall with any of Springsteen studio recordings. There were behind-the-scenes factors behind its remarkable intensity and ferocious speed: it was the gang’s first-ever show in Europe, and the Born to Run album cycle on which it fell was a make-or-break scenario for their future.

Bruce Springsteen — We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions

The record is thus a showcase for yet another corner of Springsteen’s vast performative gift: though he might never have set foot in a Greenwich Village coffee house in his youth, he inhabits this selection of antique material (“John Henry,” “Erie Canal,” “Pay Me My Money Down”) like an old hand. And he brings a savvy as a bandleader that Dylan never had to the table: the E Street Band is absent, but he still whips the “Sessions Band” up into a party over and over again.

Vangelis — Blade Runner [Original Soundtrack]

A showpiece for the remarkable capacities of what some consider the greatest synthesizer ever made: the Yamaha CS-80, which can still fetch $50,000 on the secondary market today. In Vangelis’ hands, it does serene, dreamy blues (“Blade Runner Blues”), eerie tension (“Blush Response”), heavenly glow (“Main Titles”), and more, building a remarkable sonic counterpart to the film’s dark, smoky mood.